Not Your Jane Doe: The Autonomy of a Dead Girl

By Amelia Cavanagh

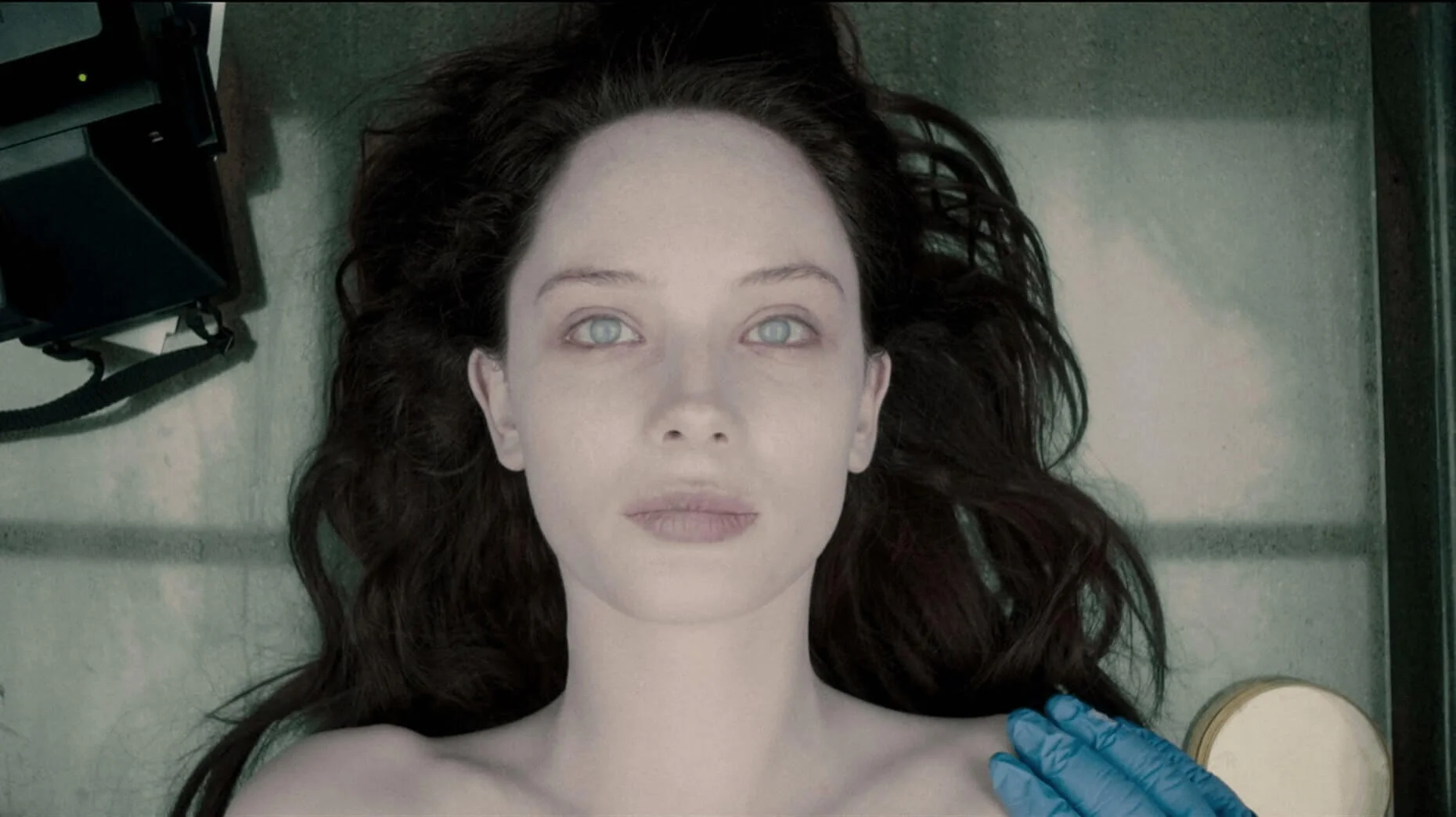

The Dead Girl is a classic demonstration of media enforced objectification. This trope hijacks the autonomy of the female victim and manipulates the audience’s empathy towards her brutalisation, resituating it as an impetus for male growth. It is a more extreme representation of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl; except this time the woman does not need to be alive to serve as the catalyst for the male character’s self-discovery. The Autopsy of Jane Doe was released in 2016 at the height of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl resurgence and continues a trend as old as media itself – the boundless Dead Girl.

The Dead Girl is a term popularised following the unprecedented success of Twin Peaks (1990) and attempts to explain the cultural obsession of centring a piece of media around the death of an – often one-dimensional, mysterious – girl, whose sole purpose is to propel the plot, which concentrates around the development of the male main character. Twin Peaks launched the term into the social lexicon and remains the best example of the trope. The story centres around the death of Laura Palmer, the mysterious and damaged Home-Coming Queen, whose naked corpse is found on the bank of a river. The story then evolves with the two Main Male Characters uncovering clues pointing to the continued brutalisation of the victim – Laura Palmer – which serves as somewhat of a background story in favour of the personal growth and exploration the two detectives undergo.

And while the term may be a recent one, the horrific and oddly compelling brutalisation of women - idealised as great, lasting beauties despite the violence of their last moments - can be seen throughout history. Early examples include the notorious tale of Medusa, a woman cursed following an assault by Poseidon and then later beheaded by Perseus on his path to ‘greatness’; Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, immortalised in John Everett Millais’s 1851 painting of the character; and the infamous Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), which sets the story along a path littered with the bodies of numerous, brutalised women.

However, when I watched The Autopsy of Jane Doe it was immediately clear to me that this, otherwise ordinary, horror film was an act of vengeance for Dead Girls everywhere. It endeavours to subvert this violent, and unjust, trope. While the Dead Girl acts as momentum for the plot of the story, this now cult classic film undergoes a series of stages which aim to unravel this emblem of violent patriarchal media. In just under 100 minutes, this film allows us to confront our de-sensitivity towards the brutalisation of the female form, as Jane Doe slowly but surely regains her autonomy – despite being a corpse.

The othering of Jane Doe by the two male characters gradually exposes their internalised misogyny, to make audiences subconsciously aware of their own objectification of this victim – Jane Doe – and by extension their objectification of all Dead Girls. We witness these male characters referring to her as a ‘female’ not a woman, despite demonstrating just a few scenes earlier that they were capable of referring to a male cadaver as a man. Additionally, the two morticians display a stomach-turning cavalier attitude towards the manner of Jane Doe’s death, which we slowly discover has been violent, brutal and inhumane, going so far as to brush off the severity of the possible cause of death, sex-trafficking. These men reflect our own personal de-sensitivity that is result of the oversaturation of violence against women.

The film makes the audience confront its numbness towards female violence, which is further reflected in the brutal death of the younger man’s girlfriend. Jane Doe tricks the younger man into believing she is lurking in the halls, coming steadily closer to the agitated young mortician who, brandishing an axe, strikes a killing blow, fearing his death is imminent. Once the fog lifts, we are made privy to the truth, which is that the woman in the halls was never Jane Doe, but the mortician’s young girlfriend who arrived for their agreed upon date. While media cleverly distorts us into believing abject violence against women is normal, if not deserved, this scene allows audiences to reflect on their willingness to view such violence as routine.

The audience is subjected to numerous close-ups of Jane Doe’s face, body and trauma as the men slowly unravel the mystery behind her demise – this is an acknowledgement that Jane Doe is conscious of all that is being done to her, as the film unravels the truth. She is aware of her pain but is unable, at this stage, to act on it. We are then made to dismiss our empathy for her as the men, outrageously, declare that the violence enacted “happened to her for a reason” – a victim blaming sentiment that women will be all too familiar with. Their refusal to award Jane Doe with any humanity, beyond her being a task they must complete, is demonstrative of her existence as a means to the male character's end – an obvious nod to the Dead Girl trope.

Jane Doe reclaims her body and identity throughout the film, slowly stirring up violence as she subverts the reductive Dead Girl plot. She gains this agency by enacting disorder and instilling fear in the men, a rewarding twist on traditional Dead Girl media, that gets us cheering and revelling in the violence. Women’s trauma in film is too often misused as men’s reward. However, The Autopsy of Jane Doe allows women to reclaim this trauma in all its violence and shock in a way that signals strength and retribution. While women are made to cast aside their own discomfort at watching our bodies be brutalised on screen for male enjoyment and self-discovery, The Autopsy of Jane Doe allows us to embrace our power and reclaim our autonomy.

Amelia is a young writer based out of Sydney, Australia. She is currently completing a Bachelor of International Law with a minor in Spanish. She has a keen interest in social issues and media representation, writing essays about these topics in her free time and hopes to publish more as she nears the end of her degree.

We've been going independently for years now, and so far have self-financed every single project. In order to do more work, and continue supporting amazing filmmakers in the genre space, we've launched a Patreon.

If you are able to support us and the work we do on Patreon, we'd truly and deeply appreciate it.